The map of the oldest light in the universe shows intriguing deviations from expectations. Will these oddities be explained away or are we at the beginning of a revolution in cosmology?

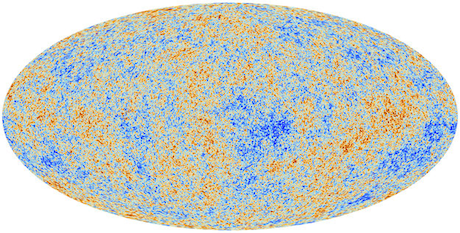

The map of the cosmic microwave background radiation revealed today by the European Space Agency's Planck mission. Photograph: ESA and the Planck Collaboration

The map of the cosmic microwave background radiation revealed today by the European Space Agency's Planck mission. Photograph: ESA and the Planck Collaboration Today is a great day. The European Space Agency has released the most precise map so far of the oldest light in the universe. The best news is that is reveals an 'almost perfect universe'. By that they mean it almost conforms to expectations – but not quite.

While the basic 'big bang' picture of our universe's birth is confirmed, the unexplained aspects of the data are where the real excitement lies because these could be signposts to new physics. At the press conference this morning, Professor George Efstathiou, University of Cambridge, UK said that the Planck data showed that, 'Cosmology is not finished.'

In an accompanying video, he even speculates that some of the strange data could be evidence of physics that took place before the big bang. This explosive origin has traditionally been thought to be the beginning of space and time.

Although now called the big bang, Belgian cosmologist Georges Lemaître, who was the first to mathematically investigate the origin of the universe, wistfully referred to it as the 'day without yesterday'. If Efstathiou is right, however, the big bang did have a yesterday after all.

ESA say that this new map of the cosmic microwave background 'challenges some of the fundamental principles of the big bang theory.' It does this by confirming the existence of features in the map that cannot be explained by prevailing theory.

The first strange feature is that the universe's temperature appears to fluctuate more on one side of the universe than the other.

Secondly, there is definitely a 'cold spot' in the universe that extends over an area of space much larger than expected.

A third challenge is that the large scale temperature fluctuations across the entire universe are smaller than those expected from the fluctuations measured at smaller scales.

The theory that these observations challenge is called inflation. It postulates that a tiny fraction of a second after the big bang, the universe underwent a sudden catastrophic expansion. This behaviour was invented to explain why the temperature of the microwave background appeared, at the time, to be so uniform across the entire universe, and on all cosmic scales.

Now, Planck is showing that the temperature, and the fluctuations in it, are not as uniform as thought.

Another problem with inflation is that it lacks a theoretical underpinning from fundamental physics. In other words, no one can find a convincing explanation for why the universe would suddenly expand just after the big bang.

The anomalies in the Planck map announced today could be the extra clues that are needed to urge inflation into a fully fledged theory, or they could provide nails for its coffin.

Time will tell, and either way, we will have made progress.

More data is expected from Planck in about a year's time.

• Stuart Clark is the author of The Day Without Yesterday (Polygon). guardian.co.uk

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий